In the ninth century B.C., the northern kingdom of Israel was teetering on the brink. After Solomon’s death, the united monarchy had fractured; Jeroboam I’s calf‑worship in Bethel and Dan (1 Kings 12:28–33) signaled a dangerous drift into idolatry. Under King Ahab’s reign, this spiritual slide accelerated. Ahab not only promoted the worship of Baal—through his marriage to Jezebel, daughter of the Phoenician king Ethbaal (1 Kings 16:31)—but also persecuted Yahweh’s prophets. Into this atmosphere of syncretism and oppression stepped Elijah son of Tishbe.

Elijah’s sudden appearance—“And Elijah the Tishbite, of the inhabitants of Gilead, said to Ahab, ‘As the Lord God of Israel lives, before whom I stand, there shall not be dew nor rain these years, except by my word’” (1 Kings 17:1)—must have felt like thunder on a windless day. He burst forth not as a courtier or a foreign diplomat, but as a lone voice calling Israel back to covenant faithfulness.

Elijah’s Early Ministry: Bread, Ravens, and a Widow

God’s initial instructions to Elijah (“Go away from here and turn eastward and hide yourself by the brook Cherith,” 1 Kings 17:3) carried a promise of provision in the wilderness. Day after day, ravens delivered bread and meat to him—an unusual drama that underlined God’s sovereignty over creation. When the brook dried up (a visual reminder of 1 Kings 17:1), Elijah was sent to Zarephath, where a widow’s last handful of flour and oil miraculously sustained both her household and the prophet (1 Kings 17:8–16).

Theologian John Calvin reflects on this episode: “Elijah is not only fed himself, but becomes the instrument to sustain the widow’s life; thus God’s bounty is ever-widening” (Calvin, Commentary on Kings). Likewise, Matthew Henry marvels that the miracle teaches us dependence: just as the flour did not waste, so the Lord’s resources are inexhaustible.

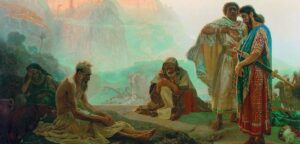

The Confrontation at Mount Carmel

Elijah’s most dramatic moment arrives in 1 Kings 18. On Mount Carmel, he challenges 450 prophets of Baal to a divine duel. Two altars stand side by side beneath an ominous sky: one to Yahweh, one to Baal. The terms are stark—each side prepares a sacrifice without fire; the true God will ignite the offering.

From morning until noon, the prophets of Baal cry, dance, even slash themselves—yet no response. Then Elijah drenches his offering with water three times over, not out of skepticism but to magnify the forthcoming miracle (1 Kings 18:33–35). With a brief, fervent prayer, fire descends, consuming the drenched sacrifice, wood, stones, dust, and even the water in the trench around the altar (1 Kings 18:38). The people fall prostrate: “The Lord, he is God; the Lord, he is God” (1 Kings 18:39).

Walter Brueggemann observes that Mount Carmel is more than spectacle; it’s a theater of exile and restoration. Through Elijah, Yahweh claims Israel’s loyalty by a display of power that forces choice—no middle ground allowed.

Flight, Despair, and the Whisper of God

Despite his triumph, Elijah’s career takes a darker turn. Queen Jezebel vows his life, and he flees into the wilderness, despairing even of life itself: “It is enough; now, O Lord, take away my life” (1 Kings 19:4). Yet an angel ministers to him with bread and water, reminding us that God often meets us at our lowest ebb.

At Mount Horeb, Elijah expects God to speak in fire, wind, or earthquake—but instead encounters “a sound of sheer silence” (1 Kings 19:12). This “still, small voice” suggests that divine guidance often comes quietly, beneath the roar of our fears. As theologian James Kugel notes in The Bible As It Was, this moment reframes prophecy: it’s not only about dramatic signs, but about inward attentiveness to God’s subtle leading.

Passing the Mantle: From Elijah to Elisha

Elijah’s ministry culminates in an extraordinary departure. Crossing the Jordan with his protégé Elisha, Elijah strikes the riverbed with his rolled-up cloak, parting the waters (2 Kings 2:8)—echoing Moses at the Red Sea. Approached by a chariot of fire and horses of fire, Elijah is taken up into heaven in a whirlwind (2 Kings 2:11). Elisha picks up the fallen mantle, crying, “My father, my father, the chariots of Israel and its horsemen!” (2 Kings 2:12), thus beginning his own prophetic journey.

Here lies a pattern repeated throughout Scripture: the call to succession, to carry forward the torch of faithful witness. In early Jewish tradition, Elijah’s ascent becomes symbolic of hope for future redemption; the Talmud anticipates his return as herald of the Messiah (Tractate Sanhedrin 98b).

Elijah’s Theological Significance

Elijah emerges as a type of eschatological forerunner. Malachi’s prophetic oracle declares, “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the great and awesome day of the Lord comes” (Malachi 4:5). In the New Testament, Jesus links Elijah to John the Baptist (Matthew 11:14), implying that the spirit and power of Elijah reappear to prepare hearts for the Messiah.

John Calvin interprets this typology: Elijah’s ministry of judgment and restoration foreshadows Christ’s own work of purging sin and establishing a new covenant. And in Revelation 11, the two witnesses (often identified as Moses and Elijah) continue this theme, testifying and performing signs before the final judgment.

Elijah in Jewish and Christian Memory

Within Judaism, Elijah’s memory lives on in the ritual of the Passover Seder. A cup of wine is set aside “for the prophet Elijah,” and the opening of the door invites his symbolic arrival, a gesture of messianic hope. In Christian iconography, Elijah’s fiery chariot has inspired countless paintings and hymns—reminding believers that God’s messenger transcends earthly constraints.

Modern scholarship—such as Richard Nelson’s First and Second Kings commentary—tends to view the Elijah narratives through both historical-critical and literary lenses. Nelson argues that these stories were shaped during or after the Babylonian exile, offering a paradigm for faithful resistance against assimilation and idolatry.

Lessons for Today

Why study Elijah? First, his uncompromising stand reminds us that faith often demands costly witness. In a culture that prizes compromise, Elijah models the courage to say “No” to false gods. Second, his journey from triumph to despair shows that even the greatest servants of God can struggle with loneliness and discouragement.

Finally, Elijah’s story teaches us to listen for the “still, small voice.” In our noisy world—filled with constant alerts and clamoring opinions—the true prophethood may emerge in quiet, interior spaces where God gently calls.

Conclusion: The Echo of a Whirlwind

Elijah’s life is a tapestry of fire and whisper, of dramatic confrontation and hidden consolation. From his fearless challenge on Mount Carmel to his tender encounter at Horeb, he embodies the tension between public spectacle and private devotion. His ascent in a whirlwind bids us look beyond the visible, toward a future where God’s presence is fully revealed.

In the end, Elijah stands at the crossroads of history and eschatology. He is both a man of his time—addressing the idolatry and injustice of ancient Israel—and an eternal figure whose call to faithfulness still resounds. As we reflect on his story, we discover not only a colorful chapter in the annals of prophecy but also an invitation: to stand firm in our convictions, to find sustenance in God’s unexpected provisions, and to remain ever attentive to the quiet voice that guides our way.

Recent archaeological findings in the region of ancient Israel have provided new insights into the cultural and religious practices during Elijah’s time. Artifacts suggest a complex interplay between local traditions and foreign influences, highlighting the challenges Elijah faced in advocating for monotheism. Additionally, contemporary scholars are exploring the psychological dimensions of Elijah’s experiences, particularly his moments of despair, offering a deeper understanding of the prophet’s humanity and resilience.

In modern interfaith dialogues, Elijah is increasingly recognized as a bridge figure, respected in both Jewish and Christian traditions. His story is used to foster conversations about shared values and the importance of standing against moral and spiritual compromise in today’s diverse religious landscape.

Elijah’s story is a powerful reminder of faith and resilience. His life, filled with dramatic moments and quiet revelations, continues to inspire those who seek courage and guidance in their spiritual journey.